The incredible challenge of convicting the first man for rape as a weapon of war

Godeliève Mukasarasi promised God that if her children survived the Rwandan genocide of 1994, she would perform charitable acts.

They lived.

Soon after, the then 35-year-old social worker and mother founded SEVOTA, or Solidarity for the Development of Widows and Orphans to Promote Self-sufficiency and Livelihoods, a support group for local women of the small village of Taba, in central Rwanda, to heal from the emotional scars of a massacre that left roughly 1 million people dead and up to 500,000 women raped over the span of 100 days.

Mukasarasi’s story and that of several other individuals is spotlighted in producer and co-director Michele Mitchell’s documentary, “The Uncondemned.” After all, it was their combined efforts that led to the conviction and life imprisonment of Jean-Paul Akayesu, the mayor of Taba, who supervised the systematic rape and torture of women in the same building where he once served as a civil servant. Akayesu’s case was the first successful prosecution of rape as a crime of war.

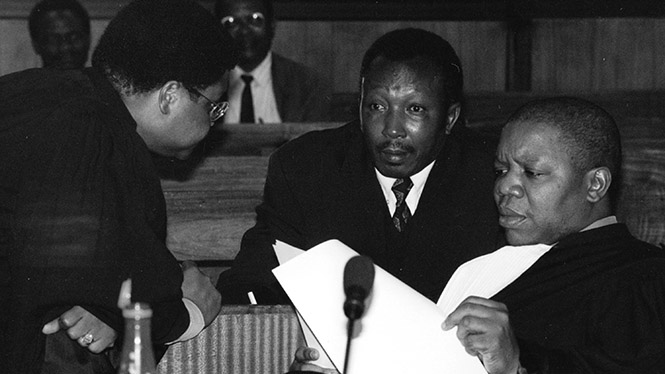

In 1996, Akayesu stood trial for 15 counts of genocide, crimes against humanity, and rape during the Rwandan genocide as well as for violations of the Geneva Conventions. Thanks to witness testimony, the tribunal found him guilty two years later of nine counts of genocide and crimes against humanity.

At least 1 million were killed and 500,000 women raped in a span of 100 days during the Rwandan genocide. (Courtesy “The Uncondemned”)

The trial—and the mountains of challenges the witnesses faced in coming forward—is meticulously reconstructed in “The Uncondemned.” Mitchell, an investigative journalist, and her late co-director Nick Louvel, tell the story through interviews with key players in what becomes a suspenseful courtroom thriller on how a group of underdogs won the day. Yet the film also exposes how the voices of the survivors were repeatedly ignored.

For starters, why did it take so long for rape to be taken seriously as a war crime by the international community, despite overwhelming evidence that rape had been used systematically as a tool of torture previously in the Bosnian conflict? The Rome Statute, upon which the International Criminal court is built, clearly lists rape as number seven in a list of crimes against humanity.

And even as the case against Akayesu was finally being prepared, activists had difficulty convincing the prosecution to amend the charges to include sexual assault. Binaifer Nowrojee, a former Human Rights Watch researcher, whose report, “Shattered Lives,” projected the voices of Rwandan rape survivors around the world, is visibly exhausted when describing her frustration in the film.

“It’s not rocket science,” she exhales.

When Lisa Pruitt, an American lawyer and rape crisis counselor, arrived in Rwanda to act as a gender consultant for the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, she was appalled to learn how female witnesses had been treated by mostly male, white investigators. “They were being dismissive of these women as credible witnesses,” she told me over the phone. “That was really offensive to me, in part because I empathize with these women and in my work as a rape crisis counselor in the States—I had seen female rape survivors treated the same way by police officers.”

Pruitt wrote a series of memos that detailed how to draw better testimony from women who were still traumatized. Although her work would prove to be vital to the Akayesu case, her suggestions, at the time, were summarily dismissed. Later Pruitt would reveal that she herself had been sexually assaulted by a college acquaintance. “I wanted these women to be taken seriously and I suppose that’s a proxy for not having been taken seriously as a rape survivor,” she said.

I asked Mitchell why the world seemed—and even still seems—so intent on remaining deaf to the voices of women who survive rape in conflict. “There is something very difficult about having it spelled out for you what rape in conflict is,” she said. “It is so clearly an act of torture when you hear it, right? The [general public has] no idea that this goes on, and let’s face it, most people don’t really want to know what’s going on in war.”

Mitchell said she battled a sense of hopelessness throughout the making of the film. “There was this moment where a woman in a fistula ward [in Goma, in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo] asked me: Does the world really want to hear our story? I remember telling her, ‘No. The world doesn’t want to hear your story, but I promise you I’m going to figure out a way to tell this in a way that the world wants to hear. And they will hear you, and they will understand on an intrinsic level what rape in conflict means.’”

One of the key witnesses, Victoire Mukambanda, recalls in the film the indignity of her own interrogation by legal investigators. She says that she didn’t open up to the investigators at first because the way they spoke to her made her uncomfortable. She is steely-eyed, her chin perched atop her folded hands. “We thought they knew the story [of the rapes] and they were mocking us,” she tells an off-screen interviewer.

Mukambanda was one of three women who would brave the threat of retaliation to come forward and testify against Akayesu. She was joined by Serafina Mukakinani and Cecile Mukarugwiza, who was only 17 at the time of the trial. The three women had been bolstered by Mukasarasi’s work at SEVOTA. Yet it is unclear in the film whether they were aware during the trial that Mukasarasi’s husband had been murdered as he was preparing to testify against the same man.

The women testified, protected only by a thin curtain. But was the world finally ready to hear them?

It turns out it was.

Jean-Paul Akayesu, seen here in court, was found guilty of nine counts of genocide and crimes against humanity. (Courtesy "The Uncondemned")

The small-town-mayor-turned-war-criminal was sentenced to life in prison. He is currently serving his sentence in Mali. Today, the witnesses, who previously were known only by the letters assigned to them to hide their identities, travel the world to speak out on behalf of victims.

I called Mukambanda, Mukakinani, and Mukarugwiza just before a speaking engagement they had at Texas University. With the help of an interpreter, I asked what had given them the courage to speak out so long ago even when it seemed no one was listening.

The women told me that, at first, they found strength in togetherness, then were spurred on by the knowledge that there were other victims who would never be able to speak out. According to Mukambanda, “this was a way of encouraging all women to see them and not be afraid to speak out—and also for them to know that there is a way to get justice.”

“I think it’s really clear that we’re past the point of not taking [rape] as seriously as any other crime of war,” Mitchell said. “It will be taken as seriously. And if you politicians, if you military leaders, if you [the International Criminal Court] do not take this seriously as you do every other crime of war, you will be hearing about it from the public.”

I asked Mitchell—does she think the film can really help bring about more serious execution of a law that has been on the books for almost a century?

She’s optimistic. “It has to,” she said.

More articles by Category: International, Violence against women

More articles by Tag: Law, Rape, Men, Sexualized violence