Oscar and the Usual Suspects

Women's absence from Best Director nominees only reflects the industry's dismal hiring statistics, as demonstrated in the author's annual Celluloid Ceiling study.

With this year’s Academy Awards ceremony just around the corner, Oscar has rounded up the usual suspects for filmmaking’s most prestigious honor. Not surprisingly, the demographic profile of the nominees for the coveted Best Director award closely resembles that of the academy’s governors. As Michael Cieply states in a New York Times’ Carpetbagger blog, "All are male, all are white, and most have been a presence at the Oscars before." He also notes that the average age of the nominees mirrors that of the academy’s governing board.

In other categories, women who direct earned nominations in the documentary short subject category (Robin Fryday and Gail Dolgin for "The Barber of Birmingham: Foot Soldier of the Civil Rights Movement"; Rebecca Cammisa and Julie Anderson for "God is the Bigger Elvis"; Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy and Daniel Junge for "Saving Face"; Lucy Walker and Kira Carstensen for "The Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom"). And Jennifer Yuh ("Kung Fu Panda 2") is among the directors of the animated features nominated for an Oscar.

But all of the tallies and the resulting horserace coverage distract from a larger issue. The annual under-representation of women on the list of Oscar nominees is merely a symptom of the larger illness ailing the mainstream filmmaking industry in this country. According to the annual Celluloid Ceiling study released by the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film, women comprised only 18 percent of all directors, executive producers, producers, writers, cinematographers, and editors working on the top 250 domestic grossing films in 2011. This represents an increase of 2 percentage points from 2010 but a decrease of one percentage point from 2001.

By role, women accounted for 5 percent of directors, 14 percent of writers, 18 percent of executive producers, 25 percent of producers, 20 percent of editors, and 4 percent of cinematographers last year. The abysmally low number of women working as directors is especially troubling, as women comprised 9 percent of directors in 1998—so much for creeping incrementalism.

The bottom line is that women can’t keep company with Oscar if they’re largely unable to gain employment in key roles. It’s that simple. The filmmaking and nomination processes engage, consciously or not, their participants’ comfort levels. People feel most comfortable telling stories that reflect their own reality. People nominate individuals and stories they can relate to. There’s no grand conspiracy here. We feel most comfortable with those that look like us.

Thus, without significant intervention or motivation to change, male-dominated industries such as film tend toward a sort of demographic myopia. Since filmmaking is, like it or not, in the business of cultural transmission, this employment issue translates into a larger social dilemma. At the film and industry levels, the prolific media coverage that accompanies Oscar nominations and wins transforms mere mortals into near-mythic personalities. Because women are largely excluded from powerful behind-the-scenes positions, they are largely excluded from the nominations. In turn, their careers fail to benefit from the resulting visibility. This lack of visibility feeds the following dysfunctional myths that maintain and even strengthen the status quo: women aren’t interested in making studio films (especially tent-pole features), women self-select out of filmmaking, and films made by women and/or featuring women earn less at the box office. At the cultural level, mainstream films reflect the worldviews of a shrinking portion of the U.S. population. Men, almost all of them white, directed 94 percent of the top grossing films released in 2011.

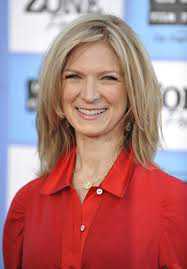

As one of the most influential and visible organizations in the film business, the academy could do more to encourage those in positions of power to provide opportunities for members of more varied social groups to tell their own stories. This year, the academy seemed to signal that it was ready for change when it appointed Dawn Hudson (pictured above), the former executive director of Film Independent, as its new chief executive. But Hudson is a single individual at the top of an organization mired in tradition, and an industry almost impervious to change. It seems likely that the most she will be able to accomplish is to nudge the academy in the right direction.

The Oscars are regularly billed as a mega-event reflecting and celebrating the best of U.S. culture. This strikes me as widely inaccurate. Rather, the Academy Awards fete films made mostly by men featuring a majority of male characters intended primarily for a male audience, that are then critiqued by a largely male group of writers and critics. Writing about Orson Welles and the "boy wonder syndrome" in a 2003 article for The Guardian, film scholar and critic B. Ruby Rich observes, "For women today, directing films is like playing against the house in a Vegas casino. The odds suck, the game is rigged." The Oscars help juice this system, reinforcing a status quo in which white men rule virtually every step in the process.

More articles by Category: Arts and culture, Media

More articles by Tag: Sexism