Bactria Revisited: Does Alexander Have Lessons for Obama in Afghanistan?

The Pakhtuns of Afghanistan and across the border in Pakistan haven’t always rejected influences from the West. The author suggests that Alexander the Great’s success in the 4th Century B.C. may hold a key to integrating Afghanistan into the international community—in a way that would help protect and empower women in the region.

Relations between President Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan and the Obama administration have reached a fever pitch in recent weeks. Karzai accuses the United States of coercion and threatens to switch his loyalties towards the Taliban. The officials in Washington accuse Karzai of corruption, ineptness and even drug abuse. Clearly our Afghan strategy—upping the military ante against Taliban insurgents while shoring up Karzai and bringing him under control—is in trouble.

Just a few months ago, a visibly troubled President Obama addressed troops at West Point: "As Commander-in-Chief," he declared, "I have determined that it is in our vital national interest to send an additional 30,000 U.S. troops to Afghanistan.

"After eighteen months, our troops will begin to come home... The struggle against violent extremism... extends well beyond Afghanistan and Pakistan. It will be an enduring test of our free society, and our leadership in the world... our cause is just, our resolve unwavering." As part of this enhanced engagement we are about to lay siege to Kandahar, the Taliban's main stronghold, and the home base of President Karzai's brother Ahmad Wali. According to the New York Times, Ahmad Wali is a major figure in the Afghan heroin trade.

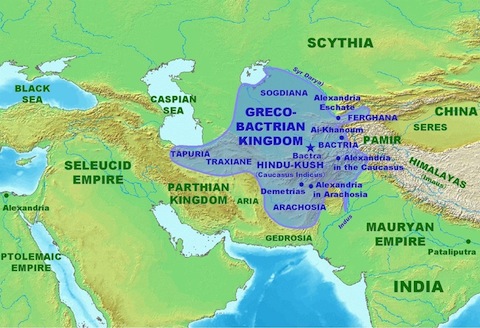

But Kandahar has another claim to fame. It is one of 30 eponymous cities established by Alexander the Great during his sweep across Eurasia in the 4th Century B.C. As we move towards Kandahar, or Iskandariya as it was then called, it may be useful to compare the international operation in Afghanistan— now in its ninth year—to his campaign.

Leading troops flush from victory over the Persian Empire, Alexander addressed them at the foothills of the Hindu Kush mountains and exhorted them onto the campaign that lay ahead. "This is a noble cause and you will always be honored for seeing it through to the end." Alexander's conquest of Bactria, today Afghanistan, is viewed in the region as the only "Western" intervention that succeeded. Alexander not only achieved his short term military objectives, but his post-conquest government lasted in South-West Asia for almost 200 years. The Bodhisattva statues in Taxila, 35 kilometers from modern-day Islamabad, have the faces of the god Apollo. Greek cultural influence is still in the region today—my grandmother used to drag us regularly to the Unani tabeeb or Ionian doctor.

With NATO countries set to withdraw troops by 2011, there is but a year to "stabilize" Afghanistan. Those in favor of withdrawal say that Afghanistan cannot be unified, that continuous tribal wars have always been the country's history, and that the local Pakhtun tribes will never accept "outside" influence. The recent defeat of the Soviet Union and past defeats of British colonialists are cited as proof.

But the same Pakhtuns once fought hard against Alexander and then accepted him as their own ruler, even deified him. Many in the region are still named after him. Sikandar Hayat is an agriculturist in Swat, Pakistan, the valley recently liberated from the Taliban by Pakistani troops, which Alexander conquered in 327 B.C. He states with pride, "My father named me after Sikander-e-Azam [Alexander the Great], he was a Bactrian Unani [Greek] King who conquered the world… but here in the lands of the Yusufzai's in Bajaur and Swat we gave him his hardest fights."

Do Alexander's campaigns offer lessons for today's stabilizers of modern Bactria? Some factors are easy to replicate. Alexander used superior technology—prefabricated boats to cross rivers and streams, bridges of boats, prefabricated siege towers—and mobilized transport on a mass scale across difficult mountain terrain to keep his troops supplied and pressing forward. The U.S. and NATO have used aerial bombing, rocket-propelled grenades and unmanned drones.

But the key to Alexander's conquests lay in three factors that the modern superpower cannot replicate. Alexander, like the ancient rulers who were his opponents, led his own troops into battle, facing the same personal dangers as his enlisted men. He was wounded several times, the last time fatally.

Additionally, Alexander secured the lasting effects of Macedonian rule long after his death by melding conquest with assimilation. Alexander became the Persian King of Kings, in dress, court and religious custom. Even more importantly, Alexander inter-married. Though the undisputed leader of Eurasia could have married into several royal houses in Greece or Persia, writes historian Frank Holt, "across the wilds of Central Asia he wed a warlord's daughter [and took on] the role of a Bactrian kinsman which undermined the rebels still opposing him." Sikandar Hayat says wistfully, "he married among us; we are an ancient people—some say we are Unani [Ionian] Pakhtuns… in the Kalash valley where his soldiers stayed on, there are still his descendants."

These are steps no NATO president or military commander can take and needs which the abstract leadership of NATO or the American state cannot fulfill. In a region where politics is personal, where alliances are still cemented by blood lines, these are important yet unspoken hurdles.

Lastly, he recruited Bactrians into his army, including some at senior levels, underscoring a message that while they were defeated, they could switch sides and join the winners. His strategy was to take Bactrian fighters with him while leaving Greek soldiers to garrison Bactria. But it was viewed as a lasting commitment rather than a trick. It is said that the souls of his veterans, the Silver Shields, still haunt Kandahar.

Paradoxically, Alexander's story would suggest that Afghanistan was an easier place to annex outright than it is to control from afar. The failed invasions of the British and the Soviets, after all, were attempts to establish a proxy state, not to absorb new territory into the mother country proper.

While NATO has non-membership arrangements in the Middle East and the NATO Parliamentary Assembly has some interaction with the Afghan parliament, NATO's mission in Afghanistan is to secure a stable yet representative regime, to train Afghan soldiers and police and thus is much closer to that of these latter day conquerors than it is to Alexander's. It is no wonder that young Afghans are confused when they compare the Alexander they are named after to the emissaries of international values today. Sikandar Raufi, a commerce student in Kabul, tells of his paternal grandfather having named him and telling him tales of Alexander's prowess: "He always implemented and achieved what he set out to do." When NATO forces withdraw next year, Afghan troops will not be ready to take on Taliban insurgents. As a result, our strategy falters.

Yet even if the United States and NATO cannot replicate Alexander's personal commitment to the Bactrian campaign or the structure of outright annexation, it may be possible to stave off civil or regional war by offering Bactrians, as Alexander did, a genuine route to join the winning side. Instead of the umbrella of empire, America and its allies must bring the Afghan campaign under the umbrella of international organizations, namely of the United Nations. The UN remains the only organization to have the membership and the respect of the United States, its NATO partners, Afghanistan, and its regional neighbors, particularly Iran and Pakistan. This is essential since no regional bodies exist to serve this role, and since Iran remains as crucial to Afghan stability as Persia was to Alexander's Bactrian success.

There are complications. The UN has no security forces; its main institutional engines can only come into gear once there is a peace to enforce and keep. But it is to the UN that post-conflict Afghanistan must be entrusted, just as was done in Burundi, Cote d'Ivoire, Central African Republic, and Sierra Leone. While cumbersome, this work in Africa shows that the UN can marry stabilizing post-conflict nations with the ability to empower those nations as partners in their own recovery.

Moreover, a strong UN role in postwar Afghanistan is the best way forward for Afghan women. The unanimously approved UN Security Council resolution 1325 requires a say for women in peace negotiation and peace settlements. The UN's development agencies work under the Millenium Development Goals—principles that make gender empowerment a priority. Meanwhile, the involvement of the UN would open doors for the activities of other international bodies. The International Criminal Court, of which Afghanistan is a state party and possibly a future source of cases, would ensure that at least in the 110 other state parties, no Afghan who commits crimes against humanity, or foreign national who commits such crimes on Afghan territory, can seek support and refuge. The crimes against Afghan women committed by the Taliban would come under this provision.

As the Obama Administration plans the end game in Afghanistan, it must develop these institutional strategies at a regional level. The best way to start that process is to begin holding peace talks in Afghanistan itself, not in far-off cities like Bonn or London. And Balkh, Alexander’s regional capital, may be a fitting host.

More articles by Category: International, Politics

More articles by Tag: Activism and advocacy