ERA? Yes! A New Push for Sex Equality

More than 70 percent of Americans think women are equally protected under the United States Constitution. We are not. As Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia put it, “Certainly the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex. The only issue is whether it prohibits it. It doesn’t.” Around the world, countries have put equal rights provisions for women into their constitutions, often at the suggestion or even insistence of the United States government—as in Afghanistan. Yet we don’t have this same provision in our own Constitution. A renewed movement for an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the Constitution is working to change this.

First proposed in 1923, the Equal Rights Amendment, with its beautifully simple text—“Equality of rights shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex” —was formulated to build on the Constitutional amendment that gave women suffrage in 1920. Passed finally by a two-thirds vote of Congress in 1972, the ERA had a seven-year deadline for ratification, subsequently extended to 1982. After a rush of state ratifications—three quarters of all states must ratify an amendment for it to be added to the Constitution—progress ground to a halt and a backlash set in.

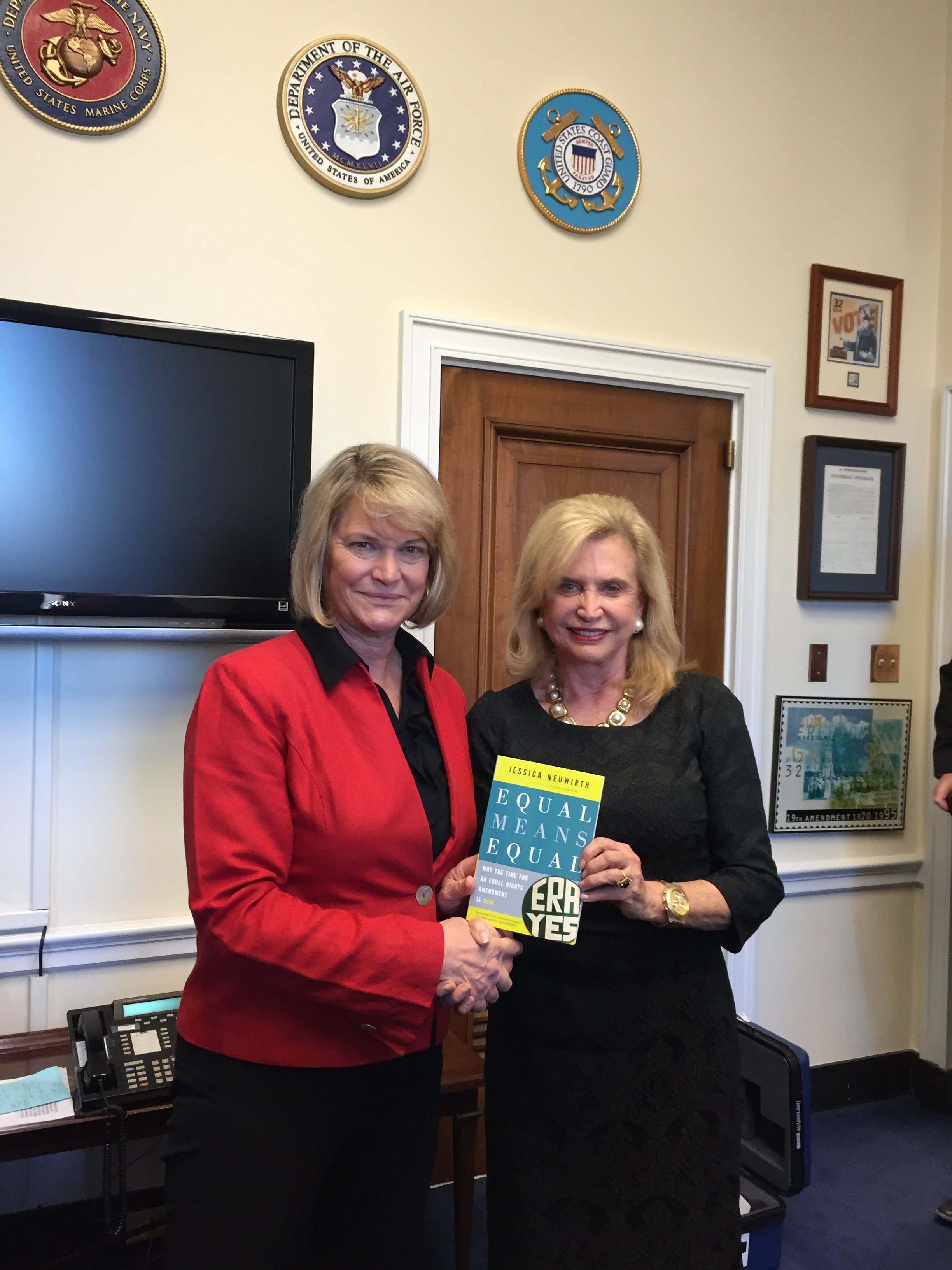

But today a new ERA Coalition is taking hold, bringing together groups and individuals across the country and working with Congress to build bipartisan support for the ERA—a proposal that is supported by more than 90 percent of Americans.

We have constant reminders of women’s unequal rights. Millions of American women each year are victims of violence at the hands of their husbands or partners. Indeed, more women have been murdered in this way since the September 11, 2001 attacks than all the Americans killed in 9/11 and in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq combined. Yet shortly after the passage of the federal Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) in 1994, the Supreme Court struck down a provision that would have enabled victims of campus sexual assault and other gender-based violence to seek justice from federal courts. The Court held that there was no Constitutional basis for this provision of VAWA. An Equal Rights Amendment could have provided the Constitutional basis for the Court to have ruled differently.

Pregnancy discrimination has recently been reviewed by the Supreme Court in the case of Peggy Young, a woman who was forced out of work by UPS after the company refused to accommodate her pregnancy. At UPS, a drunk driver who lost his license had the right to temporary reassignment without driving, while a pregnant woman had no right to reassignment to work without heavy lifting. In 1974 the Supreme Court ruled that pregnancy discrimination did not constitute sex discrimination under the Constitution: because men can’t get pregnant, there can be no discrimination. Although Congress disagreed and passed the Pregnancy Discrimination Act to clarify that at least under the Civil Rights Act sex discrimination does include discrimination on the basis of pregnancy, the recent Supreme Court decision suggests only that women may have the right to temporary reassignment if drunk drivers have that right. Women still do not have an independent right to workplace accommodation of pregnancy.

Pay inequity has also been a persistent problem, with women making on average 78 cents for every dollar a man makes. Over the course of their careers, women can expect to earn anywhere from $700,000 to $2 million less than their male colleagues. The Equal Pay Act was passed in 1963, but it allows employers to justify paying a woman less than a man doing the exact same job if she was paid less than he was in her last job. In this interpretation, the courts have disregarded, or even institutionalized, past sex discrimination resulting in present wage differences between women and men. The Lilly Ledbetter Act enabled plaintiffs who succeed in a wage discrimination case to get damages stretching back more than the last six months of their career. But to benefit from this step forward, plaintiffs have to be able to win their cases, and that has not gotten any easier as a result of the new law.

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act and the Equal Pay Act, like the Lilly Ledbetter Act, are merely laws that can be rolled back anytime, and they offer far less protection for women than a Constitutional guarantee of equality. If only three additional states had joined the 35 that ratified the ERA in the 1970s, by now we would have decades’ worth of women’s rights jurisprudence on the books. Young women would have more effective recourse for campus sexual assault, and as a result maybe there would be fewer of these assaults. Peggy Young and so many women like her might not have had to choose between having a baby and having a job.

An Equal Rights Amendment would establish the fundamental principle of sex equality as a Constitutional right. The old arguments of the 1970s against the ERA—fear of women in combat, fear of same-sex marriage, fear of gender-neutral bathrooms—are way out of date. So is the Constitution, which was written neither by nor for the people who are women.

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Ginsberg has said that it is her life’s ambition to see the ERA passed.

It’s high time to make it ours.

More articles by Category: Economy, Feminism, Politics

More articles by Tag: Equal Pay, Women's history