This new book takes on the experiences of female journalists over the decades

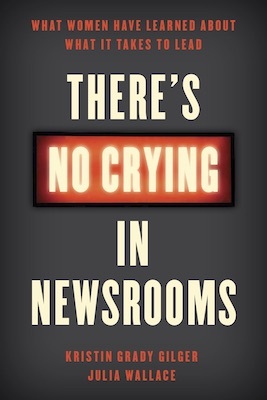

In the recently published book There’s No Crying in Newsrooms, award-winning journalism scholars Kristin Grady Gilger and Julia Wallace investigate how gender has shaped the experiences of female journalists. The authors interviewed more than 100 journalists to portray how these experiences have changed over the last four decades in the business.

Julia Wallace is the Frank Russell chair at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University and a veteran news industry executive. Kristin Grady Gilger is the senior associate dean and Reynolds professor in business journalism, also at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism. Gilger recently told The FBomb about what she found in the process of writing the book.

The FBomb: How did you and Julia Wallace come up with the idea for this book?

Kristin Grady Gilger: I have been thinking about the topic of women’s leadership, especially in newsrooms, for years. I knew a lot of women who rose into management positions at news organizations around the same time I did, and no one had really captured their stories — which are pretty hilarious and pretty devastating at the same time.

But working a (more than) full-time job, I also knew I couldn’t tackle a book on my own. When Julia Wallace joined our faculty a little more than a year ago, I knew I had found the perfect writing partner. Julia and I had worked together twice before — at the Salem (Oregon) Statesman Journal and at The Arizona Republic newspapers. Before she had even started, I called her up and asked, “So how would you like to write a book with me?” She immediately answered, “Yes,” which tells you something about why she was the perfect choice!

Between us, we have four daughters, all of whom are at the beginning stages of their careers, and we hear a lot about their experiences in the workplace — experiences that are echoed by many of the other young women whom we have taught and mentored over the years. We were struck by how many of these young women still face the same kinds of challenges that we did. And we knew they could learn from the women who came before them about how to survive and even thrive in male-dominated workplaces.

In what ways did your personal experiences working in journalism inform the book — in terms of how you approached interviews with the 100 subjects included, as well as what you decided to include in the published version?

We both know a lot of people in journalism, which tends to be a pretty small world, so we were confident that a number of them would be willing to talk to us. But there were a lot of others we wanted to interview whom we didn’t know at all.

At the beginning of the project, we drew up a list of every female leader in media we could think of — and it was a really long list. Then we just started emailing and calling. We weren’t at all sure what the response would be. After all, we were asking women to reveal very personal parts of themselves — what barriers they faced in the workplace, whether they were sexually harassed, how their careers affected their marriages and their children, whether they felt they had really been able to make a difference. To our surprise, no one turned us down. And once these women leaders started talking, it was often hard to get them to stop. I think it was the first time some of them had ever opened up about these issues.

We also wanted to make sure we got the whole story. The experiences of women differ somewhat depending on whether they came up in television, public radio, newspapers, digital media, or magazines, what generation they’re from, and their ethnic and racial backgrounds. We wanted all of their voices.

Why did you decide on the title There’s No Crying in Newsrooms?

I swear that may have been the hardest part of writing the book!

We had spent more than a year working on the book and going through one bad title after another. Finally, it was crunch time. We had about two days to give the publisher a title. That weekend, one of my daughters and I were getting our hair cut, and we spent the entire time running book title ideas past our hairdresser. As we were driving home, it hit me. A League of Their Own has always been one of my favorite movies, and there’s this iconic scene in which Tom Hanks, who plays the coach of a female baseball team during World War II, confronts one of his players who is crying on the field. He is incredulous. He yells at her, “There’s no crying in baseball!” I love that scene. And I’ve told way too many women, “There’s no crying in newsrooms.”

The wonder is that we didn’t think of it sooner. A number of the women we interviewed talked about crying at work — about heading to the women’s restroom or the parking lot to have a good cry because they didn’t feel they could show weakness in the workplace. I do think that’s changing somewhat, though. Melissa Bell, who heads Vox and is a millennial, is pretty comfortable crying in her newsroom, which has been a revelation for the women who work for her, and it doesn’t seem to have hurt her as a leader, either. Young women entering newsrooms today seem much less bothered by a few authentic displays of emotion (short of kicking trash cans or getting into fist fights) than we were, which I think is a good thing.

This book covers the experiences of women in the news industry over the last 40 years. What would you identify as the biggest changes women in this industry experienced over this time period?

Going back just a bit further: When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed, I don’t think anyone understood the impact it would have on women in the workplace. It was intended to correct horrific job discrimination based on race. At the last minute, the word "sex" (note: not gender) was added to the language. It’s a bit of a shock to see the news photos of President Lyndon Johnson signing the bill — surrounded by men. Only a handful of photos, shot with a wide lens, show any women at all, and they’re at the very back of the room.

Change, though, was slow to come. It took a series of lawsuits by women at places like The New York Times, the Associated Press, and Newsweek to convince news organizations that they had to change — in large part because they were losing those lawsuits, and that meant real money.

The suits cracked open the doors for women, and we began entering the news business in large numbers in the 1970s and 1980s. What we had to deal with was pretty outrageous. Women at Newsweek, for example, weren’t considered reporter material; they were assigned to male reporters as assistants and fact-checkers.

Julia came across a transcript of a 1973 meeting of the American Society of Newspaper Editors that perfectly illustrates what it was like at the time. The theme of the conference was “Problems in Journalism,” and an entire morning was devoted to the particular problem of women in newsrooms. The women spoke first and in a fury about being thrown out, felt up, passed over, ignored, and humiliated, and they illustrated their points with a skit that was alternately hilarious and devastating. In one exchange, a male city editor tells a woman she isn’t management material because she has periods. The woman, referred to as a “newshen” in the script, replies: “Yes, Nick, yes. Women have periods. They have commas; they have semicolons; some of them even have complete sentences.”

We’ve come a long way since then, but we still have a long way to go.

Do you think the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements have influenced conduct within newsrooms?

I certainly hope so. We actually began this book before the #MeToo movement began, but even if it had never happened, we had to talk about the reality of what happens to women in newsrooms and workplaces of all kinds. Virtually every woman we interviewed had a story to tell us, and we ended up devoting an entire chapter to the topic, given the very long list of men in media who have been exposed as harassers in the past few years.

Kate O’Brian, who went on to become a top leader at ABC News, recalled an incident during her first job at ABC when she was in her 20s. One day, she was in the control room — a small, dark, crowded space — when she felt a hand cradling her behind. At first she was so shocked she didn’t know what to do, but then she decided to go for it. She said, loudly enough for everyone to hear, "Take your hand off my ass!" The control room went silent, which doesn’t happen very often, and, very slowly, the hand backed away. She said no one ever tried that with her again.

Nina Totenberg, the legendary reporter for NPR, told us about a White House dinner at which former President Bill Clinton was seated on one side of her and a high-ranking public official on the other. “This public official puts his hand on my leg, and I’m thinking, ‘You can’t make a scene at the White House,’” she said. “What was I going to do? So I held his hand for the whole dinner. I ate with one hand. My theory was the hand couldn’t move if I held it.”

Two things are clear to us: First, that women who are now in their 50s, 60s, and 70s put up with a lot of bad and abusive behavior in workplaces and generally shrugged it off or found ways to deal with it themselves. Young women today are much less willing to put up with it; they’re much more likely, in part because of the #MeToo movement, to call out behavior and demand change.

Media based on real events in the history of journalism — like the Showtime series The Loudest Voice in the Room (2019) and a film to be released this year about deceased media kingpin Roger Ailes — have become popular in recent years. What role do you think fictionalized accounts of this history play in our general understanding of the media industry?

That’s an interesting question, and it makes me think of Good Girls Revolt, the Amazon series about the historic struggle for quality at Newsweek. The show was cancelled by former Amazon boss Roy Price, who, ironically enough, later quit in the wake of sexual misconduct allegations against him.

I think these kinds of programs can really help us go beyond the headlines and see and understand a period of history and people’s personal experiences. That’s very powerful. But it’s not new.

Julia and I were giving a talk about women leaders in news at a convention of journalism educators recently, and someone in the audience asked us about the effect of the Lou Grant and Mary Tyler Moore TV shows of the 1970s-early 1980s on perceptions of women in news. I hadn’t thought about what kind of influence those shows had on me, but I suspect they were pretty powerful. At the least, they gave me the notion that working in news was an option for a woman.

Other shows, like The Loudest Voice in the Room, serve as cautionary tales about what can happen to even the most powerful people (men) when they abuse their power.

There has been a lot of speculation about the future of journalism given the rise of digital media and high number of layoffs in the industry as well as entire publications folding. Do you have thoughts on the future of journalism — personally as well as based on the views posed in interviews you conducted in the book?

I’m optimistic. There has been a huge upheaval in media over the past decade or so, and it has been very painful for a lot of people and for our country as a whole. But new business models are emerging that hold promise, and I’m certain there will continue to be a demand for credible information and magnificent storytelling. As human beings, we crave those things. We need them.

I’m also bolstered by the many talented and smart young women and men I see every day at the Cronkite School at ASU. They are incredibly dedicated to this craft and practice we call journalism, and they’re not tied to the way things have always been done. I just know they’re going to change the world.

More articles by Category: Media

More articles by Tag: Sexism, Equality, Sexual harassment