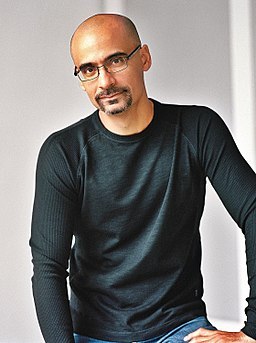

Author Junot Diaz wrote a game-changing personal piece about sexual assault

Author Junot Diaz is best known for his narrative work — most notably the award-winning novels Drown, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, and This Is How You Lose Her. While Diaz has noted that these works are semi-autobiographical, the writer published a purely autobiographical piece in a recent issue of the New Yorker. The article, titled “The Silence: The Legacy of Childhood Trauma,” recounts in detail Diaz’s experience with rape and sexual assault at the hands of a trusted adult when he was 8 years old.

Diaz penned this article directly to a fan he had briefly met at a book signing years ago. Remembering the incident distinctly, he “assumed you were going to ask me to read a manuscript or help you find an agent, but instead you asked me about the sexual abuse alluded to in my books. You asked, quietly, if it had happened to me.” Diaz spends the rest of his article describing the panic the question caused him to feel, his regret for not answering the question honestly, and, more broadly, how the abusive events about which the reader was asking followed him into adulthood.

Junot Diaz’s work centers on a character named Yunior, a Dominican boy whose father moves his family from the Dominican Republic to New Jersey, only to end up abandoning them multiple times. Throughout all three books, Yunior grows from a boy desperate for his father’s and older brother’s approval to a young man suddenly forced to come of age in the United States: He becomes a drug-dealing teenager stuck in several toxic relationships. He eventually arrives at young adulthood a guarded, cold person dangerously focused on proving his masculinity. The oldest and most mature version of Yunior the audience comes to know acknowledges that he lost the girl he loves due to his inability to stop cheating on her.

At the root of Yunior’s journey is the normally hushed topic of the expectations placed on men, especially and uniquely on men of color, to present themselves as tough, emotionless, and “macho” — and the way they’re expected to do this in the context of a present rape culture and normalization of instances of sexual abuse. Yunior exemplified this consistently throughout every book; his perspective gave readers a front-row seat to the mental and emotional toll inflicted on men of color socialized to be aggressive and apathetic, especially around their sexual identity and behavior. They wear this aggression as a mask, and Yunior’s personal account in the novels is a glimpse behind it.

Diaz, who was also born in the Dominican Republic before immigrating to New Jersey with his family to be with his father, is highly present in his protagonist. He notes in his piece that both have absent fathers, both have lost the love of their lives to infidelity, both felt an incessant need to prove they were “real Dominican men” through an excessive need to have sex all the time, and both are familiar with sexual abuse.

But for the first time, Diaz dismantles the mask he, much like Yunior, wore for years and shows New Yorker readers a surprisingly uncensored view behind it. He not only outlines the impact of being raped at 8 years old on his development into a cold, angry, and closed-off man, but goes even further: He describes the man he was at the time he wrote his now-famous books, who he was when he was discovering Yunior for the first time. Diaz describes how this “legacy of childhood trauma” manifested in a darkness that made itself known through addiction, a loss of interest in what he loved, in nightmares, in depression, and in suicidal thoughts.

Perhaps the most significant impact of this trauma, however, was how it resulted in Diaz’s own deafening silence. For years, the writer never told his family or friends about what had happened to him as a child. He never told his significant others. He never told a therapist. He never told his readers. Instead, he kept it bottled up, allowing silence in the absence of truth to create destruction and pain in his life. It wasn’t until his marriage ended and he survived another suicide attempt a few months later that Diaz finally received professional help. This help resulted in his ability to write “The Silence: The Legacy of Childhood Trauma.”

Diaz’s article is not significant just because he finally revealed the biggest secret he’d ever kept, but because in doing so he set an important example for men of color, for sexual abuse victims, or for anyone reading his article. He sent the message that the mask men are often forced to wear does more harm than good. As terrifying as it may have been to finally write, as easy as it would have been to keep up his image as a successful, untroubled writer, Diaz put his story out there for the world to see. Diaz removed his mask and broke his silence, bringing us one step closer to denormalizing the shaming of victims of sexual assault without consequence. Diaz affirmed his decision by admitting that he was “still afraid — my fear like continents and the ocean between — but I’m going to speak anyway, because, as Audre Lorde has taught us, my silence will not protect me.”

Junot Diaz ends his story with the brief account of a dream he had the night before writing the article. Rather than one of his usual nightmares, this dream featured him as the young boy he was before his rape — happy and free in his home of Villa Juana. While trauma can never truly go away, Diaz teaches us, there is a healing and a restoration of self to be found in making your voice heard.

More articles by Category: Arts and culture

More articles by Tag: Rape, Sexualized violence, South & Central America